Prohibition: 100 years ago

The 18th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution–which banned the manufacture, transportation and sale of intoxicating liquors–ushered in a period in American history known as Prohibition.

Prohibition officially went into effect on January 17, 1920, with the passage of the Volstead Act.

The Movement

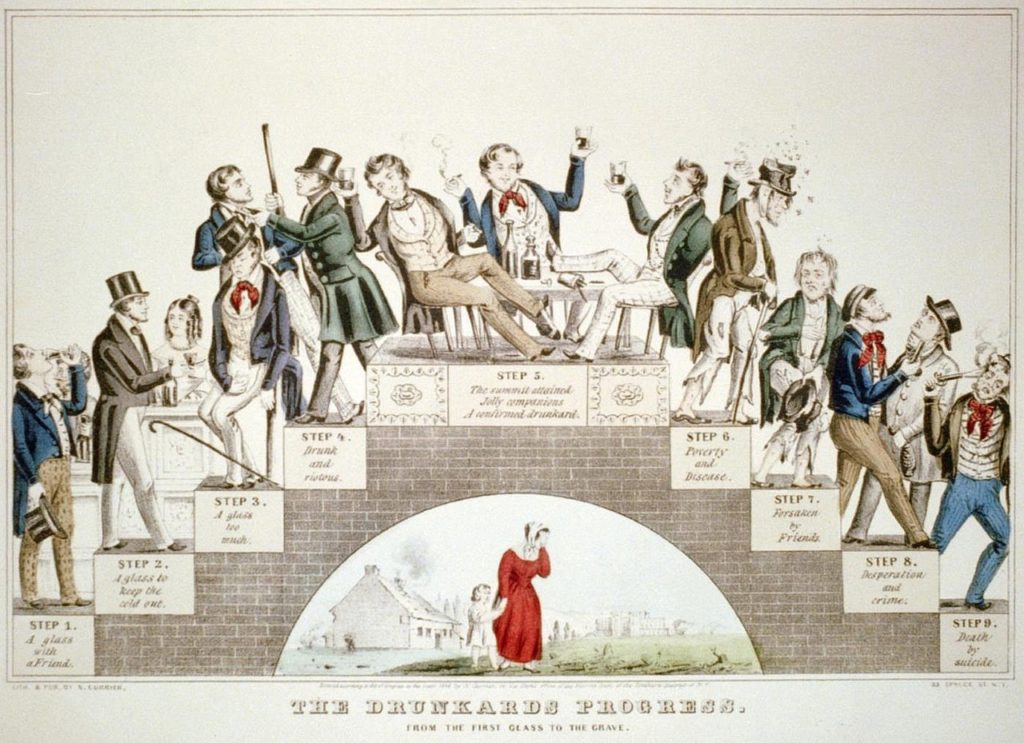

In the 1820's and ’30's, a wave of religious revivalism swept the United States, leading to increased calls for temperance, as well as other “perfectionist” movements such as the abolitionist movement to end slavery. In 1838, the state of Massachusetts passed a temperance law banning the sale of spirits in less than 15-gallon quantities; though the law was repealed two years later, it set a precedent for such legislation.

Revivalism during the Second Great Awakening and the Third Great Awakening in the mid-to-late 19th century set the stage for the bond between pietistic Protestantism and prohibition in the United States: "The greater prevalence of revival religion within a population, the greater support for the Prohibition parties within that population."

The temperance movement had popularized the belief that alcohol was the major cause of most personal and social problems and prohibition was seen as the solution to the nation's poverty, crime, violence, and other ills. Upon ratification of the amendment, the famous evangelist Billy Sunday said that "The slums will soon be only a memory. We will turn our prisons into factories and our jails into storehouses and corncribs." Since alcohol was to be banned and since it was seen as the cause of most, if not all crimes, some communities sold their jails.

Women were also major leaders of the temperance movement, arguing that alcohol made men waste money, become violent, and destroy families. Frances Willard of the Women's Christian Temperance Union called the movement a "war of mothers and daughters, sisters, and wives." Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton also created the Women's State Temperance Society. In nationalizing a cause women cared about, Prohibitionists saw their success as working hand-in-hand with progress toward allowing women to vote.

The Economic Effects

Prohibition's supporters were initially surprised by what did not come to pass during the dry era. When the law went into effect, they expected sales of clothing and household goods to skyrocket. Real estate developers and landlords expected rents to rise as saloons closed and neighborhoods improved. Chewing gum, grape juice, and soft drink companies all expected growth. Theater producers expected new crowds as Americans looked for new ways to entertain themselves without alcohol. None of it came to pass.

Instead, the unintended consequences proved to be a decline in amusement and entertainment industries across the board. Restaurants failed, as they could no longer make a profit without legal liquor sales. Theater revenues declined rather than increase, and few of the other economic benefits that had been predicted came to pass.

One of the most profound effects of Prohibition was on government tax revenues. In New York, almost 75% of the state's revenue was derived from liquor taxes. With Prohibition in effect, that revenue was immediately lost. At the national level, Prohibition cost the federal government a total of $11 billion in lost tax revenue, while costing over $300 million to enforce. The most lasting consequence was that many states and the federal government would come to rely on income tax revenue to fund their budgets going forward.

Always a Way...

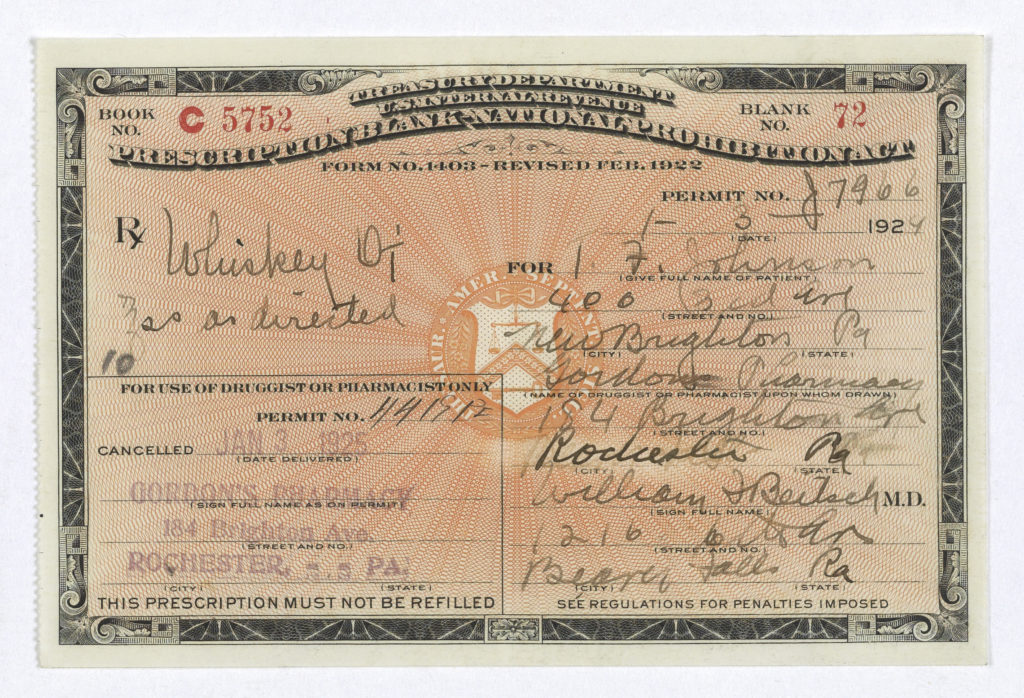

One of the legal exceptions to the Prohibition law was that pharmacists were allowed to dispense whiskey by prescription for any number of ailments, ranging from anxiety to influenza. Bootleggers quickly discovered that running a pharmacy was a perfect front for their trade.

Prescriptions for medicinal alcohol were a luxury, and

there was that pesky cap on how much you could get—unless you were Winston Churchill. Not only was his

prescription for an "indefinite" amount of alcohol, the doctor put a

minimum limit of 250 cubic centimeters (a little more than 8 ounces) on it.

Because Americans were also allowed to obtain wine for religious purposes, enrollments rose at churches and synagogues, and cities saw a large increase in the number of self-professed rabbis who could obtain wine for their congregations.

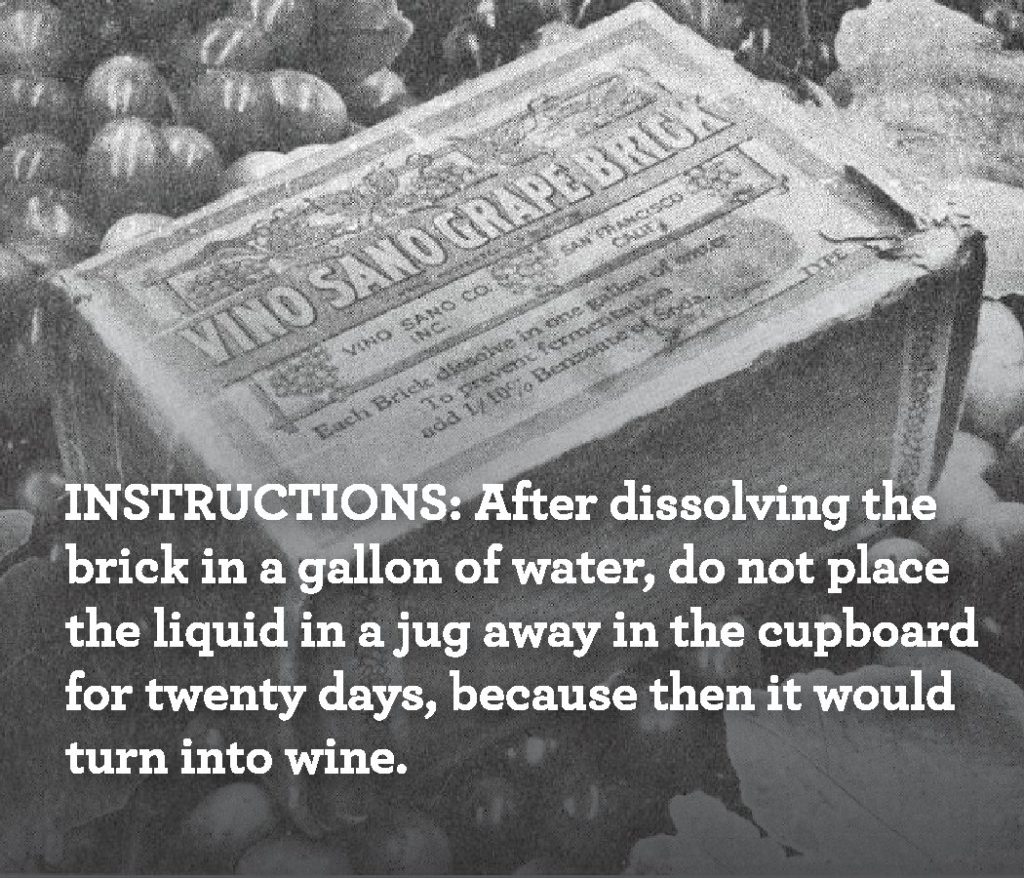

The law was unclear when it came to Americans making wine at home. With a wink and a nod, the American grape industry began selling kits of juice concentrate with warnings not to leave them sitting too long or else they could ferment and turn into wine. Home stills were technically illegal, but Americans found they could purchase them at many hardware stores, while instructions for distilling could be found in public libraries in pamphlets issued by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. The law that was meant to stop Americans from drinking was instead turning many of them into experts on how to make it.

Illegal Opportunities

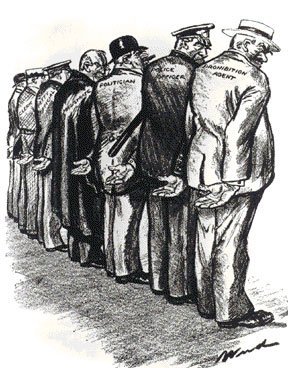

Speakeasies were generally ill-kept secrets, and

owners exploited low-paid police officers with payoffs to look the other way,

enjoy a regular drink or tip them off about planned raids by federal

Prohibition agents. Bootleggers who supplied the private bars would add water

to good whiskey, gin and other liquors to sell larger quantities. Others

resorted to selling still-produced moonshine or industrial alcohol, wood or

grain alcohol, even poisonous chemicals such as carbolic acid. The bad stuff,

such as “Smoke” made of pure wood alcohol, killed or maimed thousands of

drinkers. To hide the taste of poorly distilled whiskey and “bathtub” gin,

speakeasies offered to combine alcohol with ginger ale, Coca-Cola, sugar, mint,

lemon, fruit juices and other flavorings, creating the enduring mixed drink, or

“cocktail,” in the process

The growth of the illegal liquor trade under Prohibition made criminals of millions of Americans. As the decade progressed, court rooms and jails overflowed, and the legal system failed to keep up. Many defendants in prohibition cases waited over a year to be brought to trial. As the backlog of cases increased, the judicial system turned to the "plea bargain" to clear hundreds of cases at a time, making a it common practice in American jurisprudence for the first time.

The connection between illegal hooch and the sport of driving incredibly fast is a pretty obvious one: Moonshiners transported their illicit wares in the fastest cars they could build to evade police. Since driving fast is fun, people kept doing it even without cops on their tail, and by 1947, NASCAR was founded.

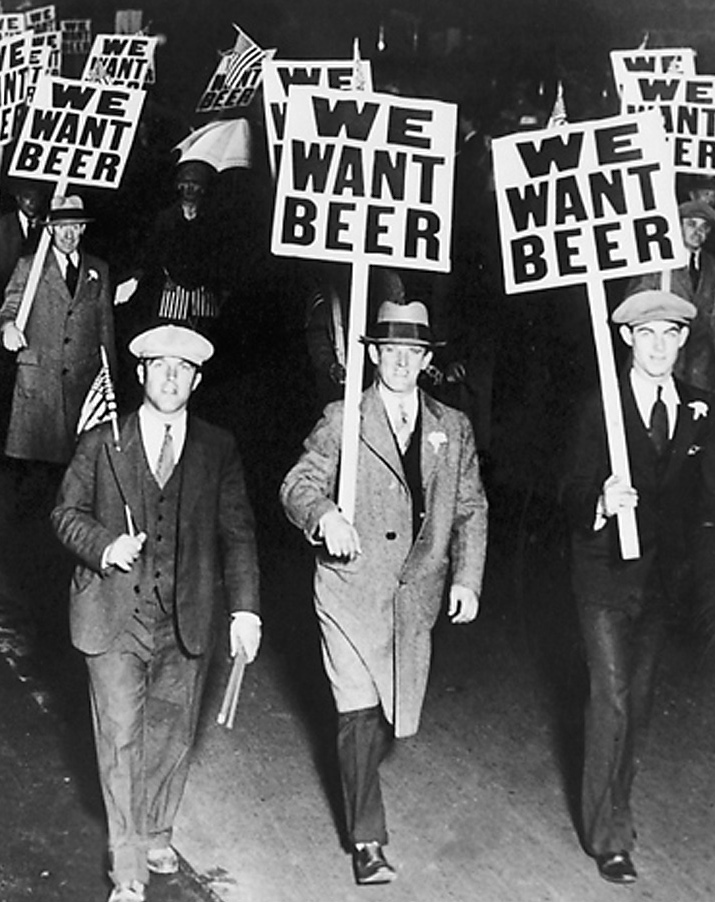

Efforts to Repeal

By 1929, after nine

years of Prohibition, many Americans were discouraged. They had long seen

people openly drinking illegal alcoholic beverages that were available almost

everywhere. They read news stories of murders and bombings in the big cities,

perpetrated by organized crime members made rich from bootlegging liquor, wine

and beer and smuggling it by land, sea and air.

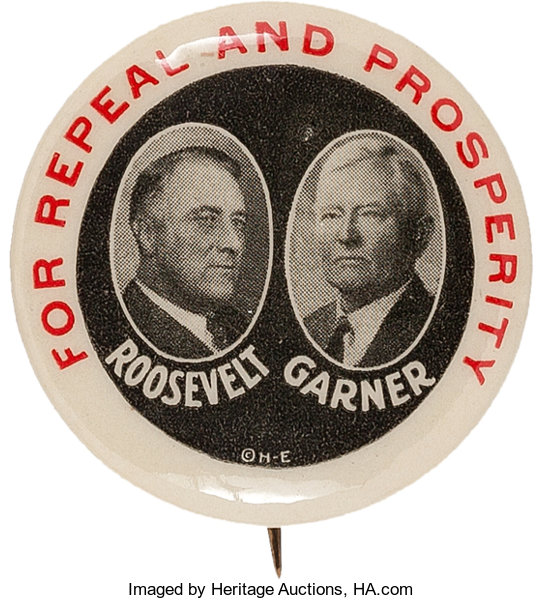

During the 1932

general election, New York Governor and Democrat Franklin Roosevelt (who had

vacillated for years on Prohibition) took advantage of both the apparent failures

of Republican policies before the Depression and the rising opposition to

Prohibition. Roosevelt’s party had a pro-repeal plank on its platform and he

campaigned for it, stating that legalizing beer alone could raise “the federal

revenue by several hundred million dollars a year.” For Pauline Sabin, repeal

transcended party identification. The Republican got her million-strong Women’s

Organization for National Prohibition Reform to endorse Roosevelt.

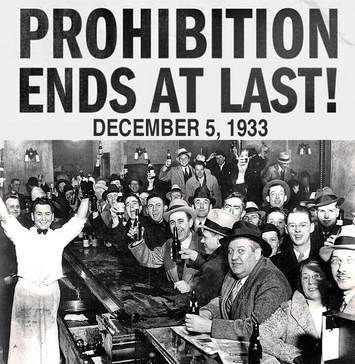

Near the end of the Prohibition Era, the

prevalence of speakeasies, the brutality of organized criminal gangs vying to

control the liquor racket, the unemployment and need for tax revenue that

followed the market crash on Wall Street in 1929, all contributed to America’s

wariness about the 18th Amendment. With its repeal via the 21st Amendment in 1933 came an end to the carefree speakeasy and the

beginning of licensed barrooms, far lower in number, where liquor is subject to

federal regulation and taxes.

Prohibition, failing fully to enforce sobriety and costing billions, rapidly lost popular support in the early 1930s. In 1933, the 21st Amendment to the Constitution was passed and ratified, ending national Prohibition. After the repeal of the 18th Amendment, some states continued Prohibition by maintaining statewide temperance laws. Mississippi, the last dry state in the Union, ended Prohibition in 1966.

Sources:

- https://www.history.com/topics/roaring-twenties/prohibition

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prohibition_in_the_United_States

- https://www.pbs.org/kenburns/prohibition/unintended-consequences/

- https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/603956/prohibition-facts

- http://prohibition.themobmuseum.org/the-history/the-prohibition-underworld/the-speakeasies-of-the-1920s/

- https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/prohibition-ends

Market Stats

Market Stats Listing Watch

Listing Watch My Home Valuation

My Home Valuation